Preface

The Association for Trans-Eurasia Exchange and Silk Road Civilization Development (ATES) Science Plan (2025–2030) offers a unique and timely opportunity to deepen our understanding of the dynamic interactions between humans and their environment along one of the world’s most storied cultural corridors. Spanning deserts, steppes, oases, forests, mountains and river systems, the ancient trans-Eurasian networks collectively known as the Silk Road have long served not only as channels for trade and communication but also as crucibles of innovation, adaptation, and cultural transformation. ATES provides an integrated scientific platform to investigate these landscapes through an unprecedented combination of disciplinary breadth and international collaboration.

What sets ATES apart from many other traditional research programs is its interdisciplinary approach, bringing together geography, archaeology, genetics, climatology, linguistics, and cultural history, to explore how human societies have interacted with and reshaped their environments over long time scales. Its research centers around six core themes, including early human migrations, the spread of agriculture, the development of towns and trade routes, the circulation of culture, science and technology, patterns of genetic and linguistic exchange, and the persistent influence of climate variability. Together, these themes illuminate long-term dynamics that continue to shape today’s challenges and opportunities.

Equally important is the model of international cooperation that lies at the heart of ATES. In an era when global challenges, from climate change and environmental degradation to resource insecurity and cultural fragmentation, require collective responses, ATES exemplifies the strength of transdisciplinary and cross-cultural collaboration. Supported by the Alliance of National and International Science Organizations for the Belt and Road Regions (ANSO) and officially endorsed as a Programme within the UNESCO International Decade of Sciences for Sustainable Development (IDSSD), ATES stands as a compelling example of science diplomacy in action.

The path ahead is both ambitious and inspiring. ATES is not only a platform for uncovering the past, it is also a catalyst for shaping sustainable and resilient futures. Its research will offer evidence-based insights into pressing global issues of adaptation, diversity, and interconnectivity, helping to bridge the worlds of science, policy, and society.

As Co-chairs, it has been a privilege to help shape this plan in close collaboration with an exceptional management and scientific team. The dedication, expertise, and vision of our colleagues have been truly outstanding. We look forward with great anticipation to the evolution of ATES and the many discoveries it will enable in the years ahead.

September 2025

Professor Fahu Chen, Professor Michael Meadows and Professor Jürg Luterbacher

Co-chairs of ATES

Association for Trans-Eurasia Exchange and Silk Road Civilization Development (ATES)

Acknowledgements

This Science Plan was developed by ATES, with Fahu Chen, Michael Meadows, Jürg Luterbacher, Ailikun and Juzhi Hou serving as the main editors. Their efforts were supported by the lead authors: Ailikun, Hao Li, Guanghui Dong, Chengbang An, Yunli Shi, Chuan chao Wang and Shengqian Chen, as well as input from many international scientists. We extend our gratitude to all the experts who contributed to the revision processes: Minmin Ma, Wei Chen, Yanan Su, Maria Sánchez Goñi, Eszter Bánffy, Deliang Chen, Nicola Di Cosmo, Radu Iovita, Hassan Fazeli Nashli, Nyamdag Ganbat, Dan Xu, Elena Xoplaki, Ruiliang Liu and Yuqing Wang, Mingjian Shen, Jishuai Yang, Linyao Du, Shuo Hao and Siyun Zhang. The idea of initiating the Science Plan originated from the first ATES Workshop on August 26-27, 2023, in Dunhuang, China. During the workshop, we discussed the preliminary strategy, structure and identified key scientific issues for each ATES working group. We sincerely thank all the contributors who participated the workshop: Fahu Chen, Jürg Luterbacher, Dongju Zhang, Radu Iovita, Hao Li, Guanghui Dong, Hassan Fazeli Nashli, Shanjia Zhang, Ting An, Bin Han, Natalia Rudaya, Hongwei Yang, Chengbang An, Quanbo Liu, Xiaofang Ma, Pap Melinda, Bill M. Mak, Wei Chen, Nyamdag Ganbat, Ailikun, Xiaolin Ren, Shuhua Xu, Shaoqing Wen, Juzhi Hou, Elena Xoplaki, Haichao Xie, Shengqian Chen, Muhammad Shafique, Ricard Huerta, Mohammad-Taqi Imanpour, Pankaj Kumar, Xin Wang, Yanbo Yu, Zhuo Wang, Mengxue Zhou, Dong Zhang, Jingyuan Feng and Ruiyang Zhou.

This work was supported by the NSFC Excellent Research Group Program for Tibetan Plateau Earth System (Grant No. 42588201) and the Alliance of National and International Science Organizations for the Belt and Road Regions (Grant No. ANSO-PA-2023-02).

Executive Summary

The Association for Trans-Eurasia Exchange and Silk Road Civilization Development (ATES) was established in 2019 under the framework of the Alliance of National and International Science Organizations for the Belt and Road Regions (ANSO) with institutional support from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Now officially recognized as a Programme within the UNESCO International Decade of Sciences for Sustainable Development (IDSSD), ATES exemplifies science diplomacy in action. It addresses urgent global challenges through interdisciplinary integration, standardized data infrastructures, cross-cultural communication, and long-term international collaboration.

In an era of accelerating environmental change, regional conflict, and threats to cultural heritage, ATES presents a timely and ambitious model for transdisciplinary research. The ATES Science Plan (2025–2030) aims to advance understanding of Eurasian history and provide science-based strategies to strengthen societal resilience across the Silk Road. It offers a framework for investigating how environmental processes, social innovations, and transcontinental networks have shaped human development over millennia.

ATES’s central mission is to explore the interactions between environmental change and the evolution of Silk Road civilizations. The program fosters integrated research across the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities, drawing upon archaeological, genetic, climatic, historical, and linguistic evidence. Its goal is to inform knowledge-based strategies for sustainable development and climate resilience in Silk Road regions.

The research agenda is organized around six core scientific themes, providing a multidisciplinary structure to investigate environment-society dynamics:

1) Paleolithic culture and human migration: Traces early human dispersals and adaptations—including Homo erectus, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo sapiens, through sedimentary ancient DNA analysis and paleoenvironmental reconstructions.

2) The origin of agriculture and trans-Eurasian diffusion of early farming and herding: Examines how domesticated crops and livestock moved between East and West Asia, enabling sedentary lifestyles. It investigates the tempo and pathways of agricultural spread, including failures, transitions, and links to the rise of social complexity and early civilizations.

3) Evolution and development of the transport networks and towns: Reconstructs the evolution of Silk Road infrastructure in response to environmental and political changes, with emphasis on trade, mobility, and urban resilience.

4) Evolution and circulation of culture, science and technology along the Silk Road: Reveals the evolution and circulation of culture, scientific and technical knowledge, including languages, scripts, epigraphic monuments, astronomy, medicine, metallurgy, irrigation, papermaking and writing systems, across regions, illuminating patterns of innovation and transmission.

5) Genetic history of Silk Road populations: Uses ancient DNA, modern genomics, and physical anthropology to analyze and reconstruct population structure, admixture, and relationships between genetics, language, and culture.

6) Human-environment-climate interactions and the impact of environmental and climatic changes on the development of Silk Road civilization and trans-Eurasian exchanges: Investigates how environmental and climatic variability and extreme events (e.g., droughts, storms, temperature anomalies) influenced societal resilience, agriculture, and trans-Eurasian connectivity.

To promote coherence and interdisciplinary depth, all research and capacity-building efforts are guided by four cross-cutting priorities:

1) Investigating human adaptation to environmental and climatic changes;

2) Assessing impacts of climatic and environmental change on civilization;

3) Advancing sustainable development, environmental management and heritage protection;

4) Developing a comprehensive, open-access ATES Database that integrates archaeological, historical, environmental, and cultural datasets.

ATES promotes collaboration through joint research and education programs, regional research hubs, and shared infrastructure. Special attention is given to training early-career researchers through scholarships, field schools, and co-supervision, supported by a network of partner institutions. The program also aligns with national and international initiatives to enhance global coordination and relevance.

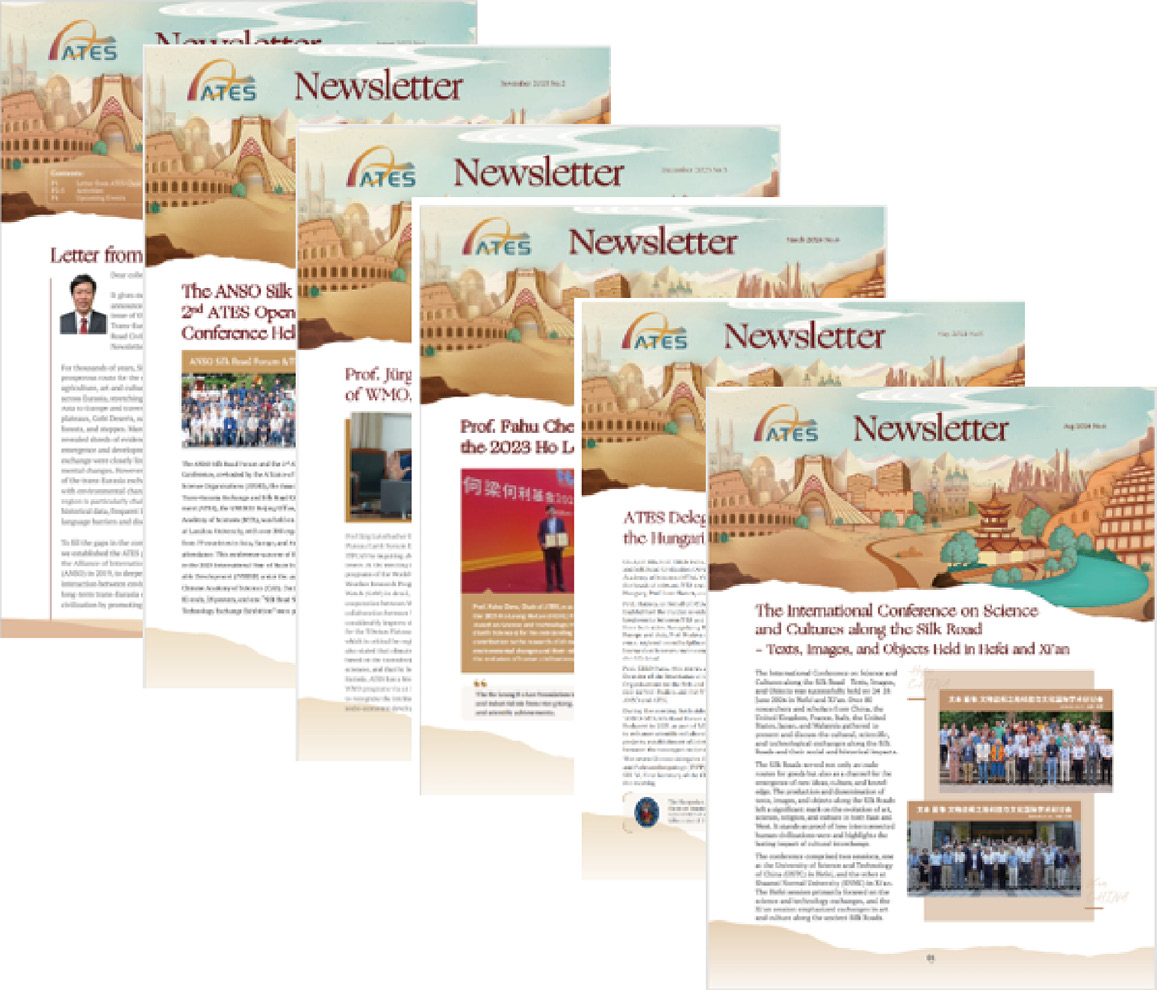

Public outreach and knowledge dissemination are central to ATES’s mission. These efforts are supported by a multilingual website, a quarterly newsletter, a suite of publication platforms, and events such as the biennial Open Science Conference and regular thematic forums. These activities aim to engage researchers, policymakers, cultural heritage institutions, and the broader public.

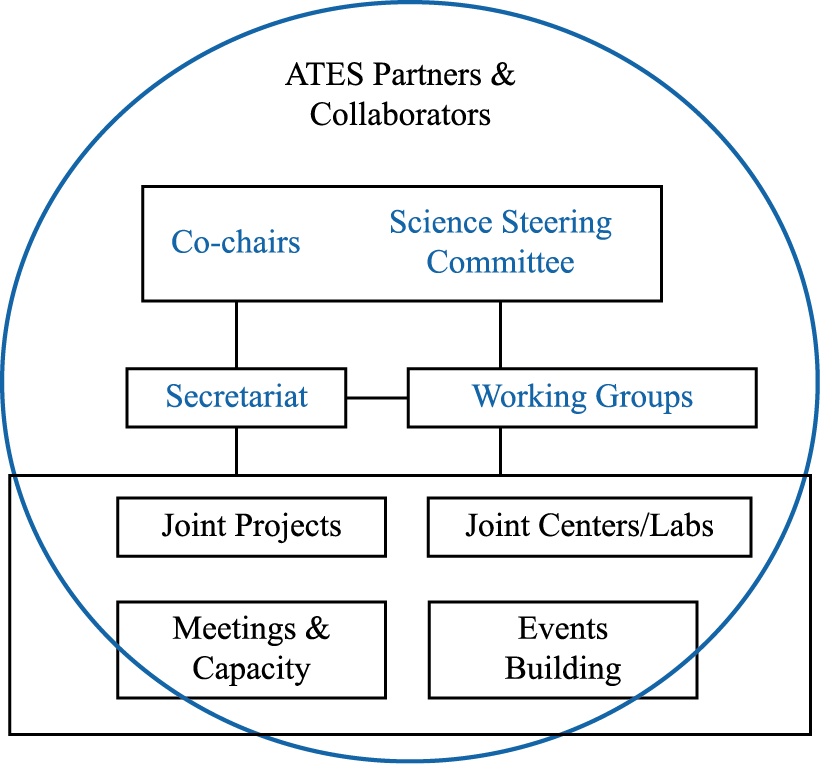

ATES’s governance structure includes Co-chairs, a Science Steering Committee, a Coordinating Secretariat, and six Working Groups aligned with the core scientific themes. These bodies provide strategic oversight, ensure coordination, and support capacity building and knowledge exchange.

List of Figures

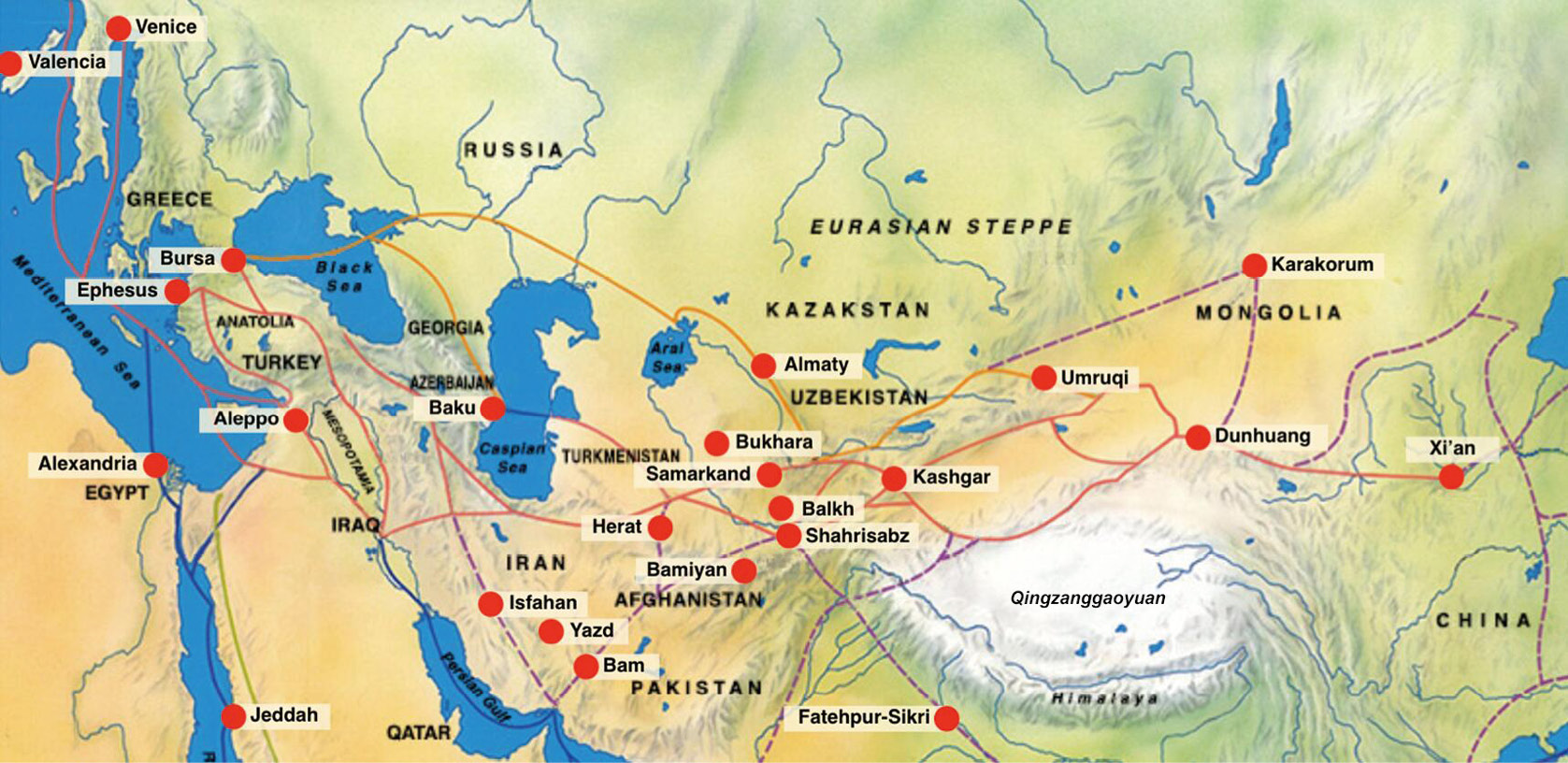

Figure 2.1 The network of trade routes and major cities across the ancient Silk Road from 200 BC to mid-15th century AD (source from Jishuai Yang, Lanzhou University, China).

Figure 2.2 Human evolution and its climate context (Timmermann et al., 2024).

Figure 2.3 The dispersals of early modern humans from Africa to Eurasia during the Late Pleistocene (Bae et al., 2017).

Figure 2.4 The spatial-temporal pattern of Neolithic and Bronze sites with crops/livestock remains originated from East and West Asia across Eurasia (Dong et al., 2022).

Figure 2.5 Distributional change of different cultures between Sintashta-Petrovka, Andronovo from northern steppe, the Oxus civilization from Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) and the Harappan civilization in Indus Valley before and after 3900 yr Before Present (BP). (A) Before 3900 yr BP; (B) After 3900 yr BP (Chen et al., 2024).

Figure 2.6 Temperature and precipitation trends (1950–2020) along the ancient Silk Road. (a) and (b) show the mean and changes in temperature. (c) and (d) show the mean and changes in precipitation. Temperature data are sourced from Climate Research Unit (CRU), while precipitation data are obtained from Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC). Dots in (b) and (d) indicate areas where the trends are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (source from Yanan Su and Shengqian Chen, Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences).

Figure 2.7 Spatiotemporal changes in the surface area of the Aral Sea (Central Asia) and Lake Urmia (West Asia) since the 1960s. Lake surface area data were derived from Landsat remote sensing images (1990–2020) with a spatial resolution of 30 m (modified from AghaKouchak et al., 2015 and Huang et al., 2022).

Figure 3.1 Interactions between Neanderthals and Denisovans in eastern Eurasia (source from Peiyuan Xiao and Hao Li, Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences).

Figure 3.2 Distribution of Neolithic and Bronze Age sites from 10.5-4 ka (a) and 4-2.2 ka (b), before and after the intensification of trans-Eurasian exchange (source from Linyao Du, Lanzhou University, China).

Figure 3.3 Major cities along the ancient Silk Road (modified from the UNESCO Silk Roads Programme, https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/).

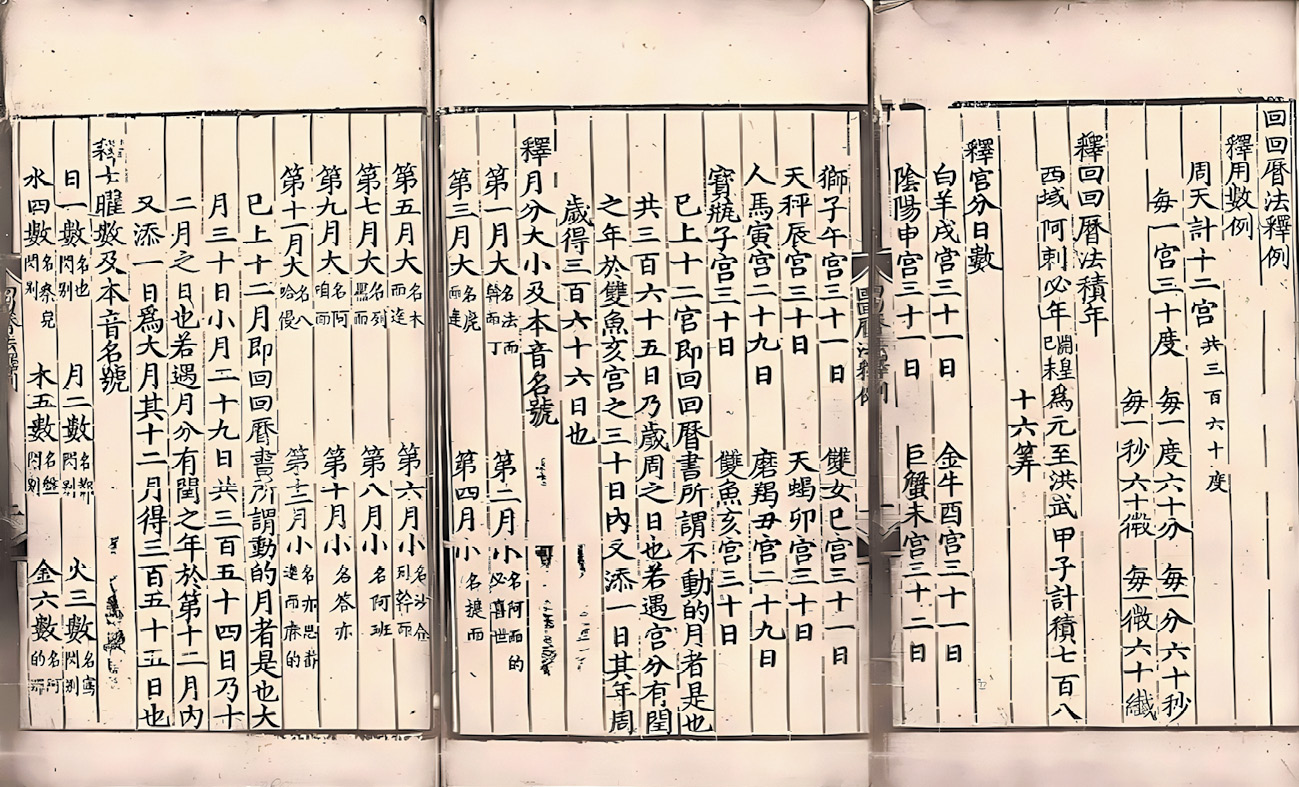

Figure 3.4 The first pages of the 14th century Chinese translation of a set of Persian astronomical tables, believed to have been compiled by the Muslim Observatory of the Yuan Dynasty in Beijing (source from Courtesy of the National Archives of Japan).

Figure 3.5 Genetic formation and migrations of the ancient Silk Road populations. Ancient Silk Road populations represent admixtures of West Eurasian Steppe herders, Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC)/Central Asians, Ancient Northeast Asians, Yellow River farmers, and Highlander-related ancestry (source from Xiaomin Yang and Chuan-Chao Wang from Xiamen University, China).

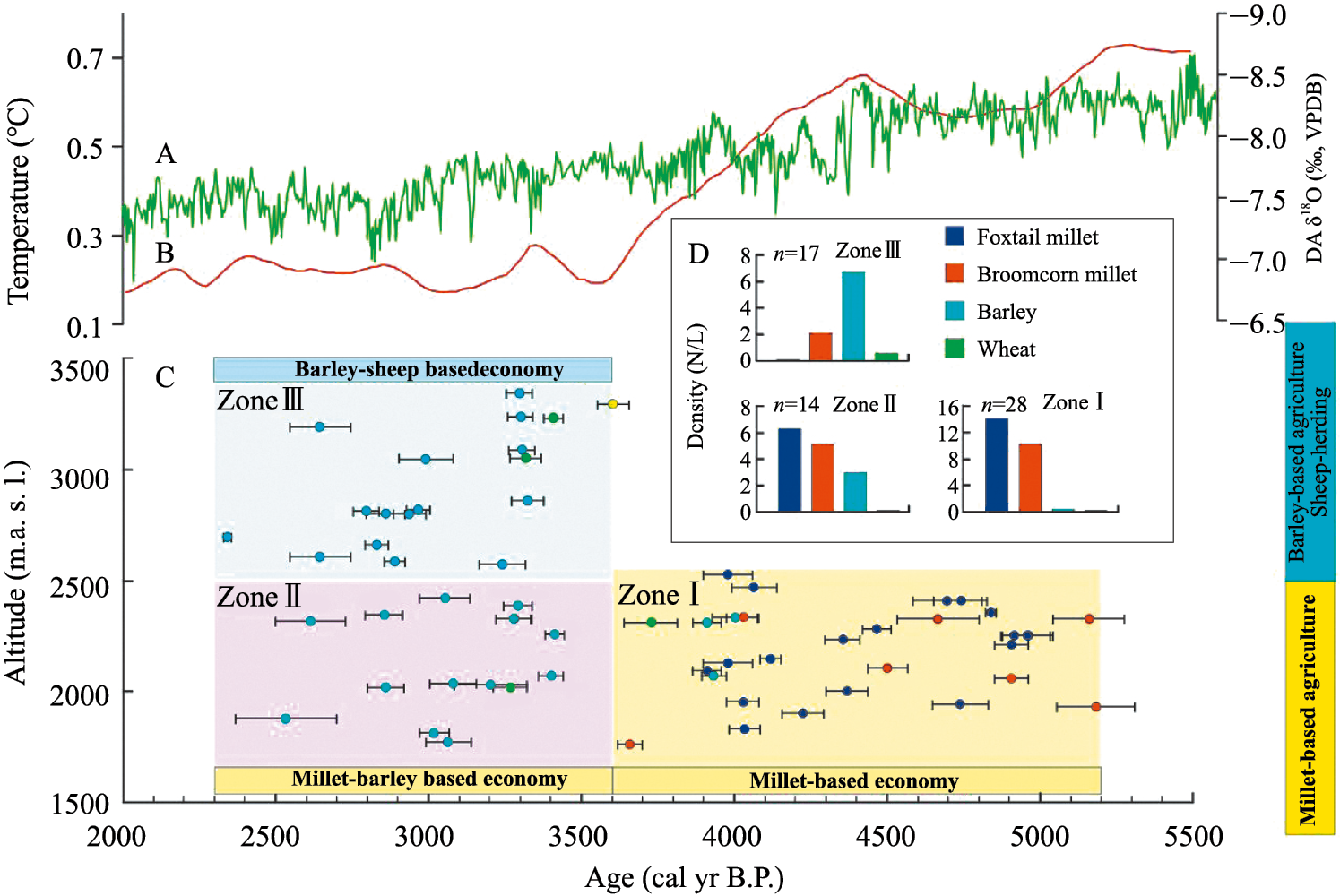

Figure 3.6 Populations expansions into higher altitude regions after 3.6 ka, driven by the adoption of barley-sheep economies (Odified from Chen et al., 2015b).

Figure 4.1 The management framework of ATES (source from ATES Secretariat).

Chapter 1 ATES Strategy, Priorities, Activities and Challenges

The ATES Science Plan (2025–2030) sets out a coordinated international research agenda aimed at advancing understanding of the complex interactions between natural and human systems across the Silk Road regions. At its core are interdisciplinary themes that examine past and present environmental dynamics, cultural landscapes, and patterns of human adaptation and resilience. By fostering collaboration and leveraging shared research infrastructure, the ATES Science Plan (2025–2030) aims to generate integrated insights that support sustainable development and cultural heritage preservation amid contemporary global challenges.

1.1 Vision

To deepen the understanding of the interactions between environmental changes, long-term trans-Eurasia exchanges and the development of Silk Road civilizations, by promoting interdisciplinary research in the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities across Eurasia.

1.2 Mission

ATES is committed to advancing cross-regional, interdisciplinary research to foster a comprehensive understanding of the Silk Road’s environmental, climatic, cultural, and socio-economic systems. By integrating field-based observations, diverse datasets, modelling approaches, and historical perspectives, ATES aims to generate actionable, science-based knowledge that supports sustainable development and long-term resilience across the Silk Road regions.

1.3 Key Scientific Priorities

1) Paleolithic culture and human migration.

2) The origin of agriculture and trans-Eurasian diffusion of early farming and herding.

3) Evolution and development of the transport network and towns.

4) Evolution and circulation of culture, science and technology along the Silk Road.

5) Genetic history of Silk Road populations.

6) Human-environment-climate interactions and the impact of environmental and climatic changes on the development of Silk Road civilizations and trans-Eurasian exchanges.

1.4 Cross-cutting Priorities

To ensure coherence and reinforce the interdisciplinary foundation of the ATES vision and mission, each scientific priority is closely aligned with the following four cross-cutting themes

1) Human Adaptation to Environmental and Climatic Changes: Investigating how human migration, food exchange, technology spread, and genetic patterns reflect adaptation across the Silk Road.

2) Impacts of Climatic and Environmental Change on Civilization: Assessing how environmental variability, particularly extreme events, influenced the rise and fall of civilizations.

3) Sustainable Development, Environmental Management, and Cultural Heritage: Exploring strategies for resilience within diverse populations, ecosystems, and socio-economic networks.

4) Development of the ATES Database on Environmental Changes and Silk Road Civilizations: Creating a comprehensive open-access repository that includes not only various sources of materials related to the Silk Road inscriptions, but also integrates historical texts, field data, paleoclimate and paleoenvironment records, socio-economic datasets, and model outputs for the Silk Road regions.

1.5 Major Activities

ATES serves as a hub for fostering international collaboration. To achieve this, it supports a range of initiatives focused on key scientific topics across Eurasia and beyond.

Joint Research

ATES facilitates and promotes international collaboration by connecting researchers and mobilizing resources for joint initiatives. Institutions and individual scientists worldwide are encouraged to initiate and develop research projects in partnership with the ATES community. In addition, ATES will establish connections with existing national and international programs and initiatives for collaboration and engagement with the broader global research community.

Joint Centers and Laboratories

In key regions integral to trans-Eurasian exchanges and the development of Silk Road civilizations, ATES seeks to establish joint research centers and laboratories in collaboration with its partners. These centers will support field observations, research activities, and capacity building. ATES welcomes suggestions for their development.

Capacity Building for Young and Early Career Scientists

A core objective of ATES is to train and support the next generation of scientists. Capacity-building initiatives include training workshops and field schools, organized in collaboration with ATES partners. ATES also promotes joint supervision of Master and PhD students and facilitates exchange opportunities for early-career researchers through support from institutions and universities within the ATES and ANSO networks. Further information can be found at: http://www.anso.org.cn/programmes/talent/scholarship. Additionally, ATES is developing an open and flexible funding mechanism to support early-career scientists conducting research at institutions affiliated with ATES collaborators and partners.

1.6 Opportunities and Challenges

ATES promotes the study of the Silk Road as a multidisciplinary priority, advancing a deeper and more integrated understanding of the region’s environmental history, cultural evolution, and socio-economic development, insights that are essential for addressing shared challenges across Eurasia.

1) Interdisciplinary integration: A key challenge lies in fostering collaboration across a wide range of fields, including climatology, geography, geology, hydrology, ecology, archaeology, anthropology, history, art, linguistics, economics, and sociology. ATES seeks to enrich cross-disciplinary education, inspire integrated research, and pave the way for policies that address climatic, environmental, social and economic dimensions.

2) Data collection and standardization: Significant gaps exist in data collection, standardization, and sharing, particularly in paleoclimate records, historical texts and documents, archaeological artifacts, and human activity datasets. Through collaborative efforts with Silk Road countries, ATES works to recover fragmented historical data, establish standardized protocols, and build interoperable platforms that overcome regional and disciplinary data silos.

3) Cultural and linguistic barriers: Cross-regional and multilingual collaboration presents challenges across different Silk Road regions. Linguistic diversity, including ancient scripts, modern dialects, and academic lexicons, complicates cross-regional knowledge exchange. The ATES platform aims to transform linguistic and cultural diversity into an asset, enabling scholars to synthesize dispersed knowledge through nuanced, context-rich analysis. A focus of ATES is to recover epigraphic monuments that document the rich cultural life of the people of the Silk Road, with special emphasis on inscriptions in languages and scripts devised by people who ruled, lived and travelled across Silk Road countries.

4) Funding and resources: Securing sustained funding and optimizing resource allocation for fieldwork, archival access, cross-border partnerships and joint scientific research remain critical challenges. ATES advocates for strategic alliances with research networks, national and international funding bodies, and heritage organizations to establish pooled-resource frameworks. These partnerships can then prioritize scalable, long-term funding mechanisms for Silk Road research.

Chapter 2 An Overview of the Silk Road

The Silk Road (Chinese: 丝绸之路), a term first popularized by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877, refers to a vast network of trade routes that connected central China to the Pamir, extending through Central Asia and Arabia to India and Rome. Active from 200 BC to mid-15th century AD (Fig 2.1), the Silk Road was originally established to facilitate trade. Over time, it evolved into the most renowned passageway (or network) in human history for exchange of languages, religions, ideas, cultures, scientific knowledge, and technologies between East and West.

Figure 2.1 The network of trade routes and major cities across the ancient Silk Road from 200 BC to mid-15th century AD (source from Jishuai Yang, Lanzhou University, China).

Spanning more than 7,000 kilometers across Eurasia, the Silk Road traverses a remarkable diversity of landscapes, including towering mountain ranges, high plateaus, arid deserts, fertile oases, dense forests, and expansive steppes. As an ancient transcontinental corridor, it stands as a powerful symbol of early globalization, where diverse environments, historical trajectories, and civilizations intersected and evolved over centuries.

Key scientific priorities of strong interest to research communities along this historic route include:

1) Paleolithic culture and human migration.

2) The origins of agriculture and the trans-Eurasian diffusion of early farming and herding.

3) The evolution and development of transport network and towns.

4) Evolution and circulation of culture, science and technology along the Silk Road.

5) Genetic history of Silk Road populations.

6) Human-environment-climate interactions and the impact of environmental and climatic changes on the development of Silk Road civilizations and trans-Eurasian exchanges.

These core priorities define ATES’s research agenda and are explored in detail in Chapter 3.

2.1 Early Humans’ Trans-continental Migration and Interaction across Eurasia

The Northwest Silk Road corridor served as a critical biogeographic and cultural route for hominin dispersals from prehistory through the Iron Age. Its distinct environmental features, shaped by fluctuating climatic conditions, presented both opportunities and constraints for early human populations. Archaeological evidence reveals a complex relationship between shifting paleoenvironmental conditions and the adaptive strategies developed by these communities (Timmermann et al. 2024) (Fig 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Human evolution and its climate context (Timmermann et al., 2024).

Early Pleistocene dispersals (~1.8-0.8 Ma) (Hereafter: Ma refers to Million years ago) of Homo erectus into northern Eurasia coincided with relatively stable climatic conditions during the 41 ka obliquity cycles (Zhu et al., 2004). The Nihewan Basin sites in northern China demonstrate these early populations’ ability to exploit diverse ecosystems (Zhu et al., 2008). The Middle Pleistocene Transition (1.2-0.7 Ma) marked a fundamental shift in Earth’s climate system, with the emergence of high-amplitude 100 kyr glacial cycles (Clark et al., 2006). The development of more extreme glacial-interglacial oscillations created a dynamic landscape mosaic that shaped hominin occupation patterns. The large glaciations at 650 ka and 450 ka (Hereafter: ka refers to thousand years ago) and the associated permafrost development may have produced a north–south ice-barrier in western Eurasia as far south as the Black Sea that could promote a genetic drift in the populations living in Eurasia and therefore the split between Neanderthals and Denisovans at that time as shown by genetic data (Sánchez Goñi, 2020).

The late Pleistocene (130-11 ka) was characterized by complex patterns of hominin occupation and interaction along these corridors. Neanderthal populations expanded eastward during MIS 5 interstadials, reaching the Altai Mountains by ~90 ka (Kolobova et al., 2020). Denisovan populations show genetic evidence of long-term persistence in the Altai-Sayan region, suggesting successful adaptation to more variable montane environments (Douka et al., 2019). The repeated genetic introgression events between these two groups (Slon et al., 2018) highlight how climatic fluctuations created periodic opportunities for population contact in this ecotonal zone. MIS 3 (~60-26 ka) represents a critical period for early modern human dispersals (Fig 2.3, Bae et al., 2017). Initial Upper Paleolithic assemblages from sites like Tolbor-16 (Mongolia) show technological innovations adapted to cold steppe environments (Zwyns et al., 2024). The Last Glacial Maximum (26-19 ka) represents the final major Pleistocene climatic event influencing hominin distributions along these routes. Extreme aridity and cold temperatures led to population contractions, with archaeological evidence suggesting abandonment of northern latitudes and concentration in refugial areas (Bazgir et al., 2017). The subsequent Late Glacial warming (15-11 ka) then facilitated re-expansion and the development of new adaptive strategies that would characterize the transition to Holocene subsistence patterns.technological innovations adapted to cold steppe environments (Zwyns et al., 2024). The Last Glacial Maximum (26-19 ka) represents the final major Pleistocene climatic event influencing hominin distributions along these routes. Extreme aridity and cold temperatures led to population contractions, with archaeological evidence suggesting abandonment of northern latitudes and concentration in refugial areas (Bazgir et al., 2017). The subsequent Late Glacial warming (15-11 ka) then facilitated re-expansion and the development of new adaptive strategies that would characterize the transition to Holocene subsistence patterns.

Figure 2.3 The dispersals of early modern humans from Africa to Eurasia during the Late Pleistocene (Bae et al., 2017).

The 10–20 ka period saw significant transformative changes in hunter-gatherer societies (Watkins, 2024; Flannery and Marcus, 2012; Matthews and Fazeli Nashli, 2022). From~15 ka onward, innovative resource strategies emerged, altering lifestyles through animal/plant domestication and climate adaptations (Zeder, 2024; Fazeli Nashli et al., 2024 a,b). Key climatic transitions included the Younger Dryas cold phase (12.9-11.7 ka) and the warmer Holocene (post-11.7 ka), characterized by reduced temperature fluctuations compared to the Pleistocene (Oldest Dryas period) (Johnsen et al., 1992; Otto-Bliesner et al., 2021). These environmental changes had profound implications for early emergence of agriculture (Degroot et al., 2022; Lyu et al., 2022, Matthews et al., 2024). Stable Holocene conditions enabled reliable food production for growing populations (Gupta, 2004; Snyder, 2016), while climatic stresses simultaneously pressured societies to diversify food sources (Zeder, 2008; Bar-Yosef, 2012). The early Holocene (~10 ka) witnessed independent agricultural emergence in Southwest and East Asia, initiating population surges and Eurasian-wide cultivation of domesticated crops like Middle Eastern wheat/barley and Chinese rice/millets, alongside animal domestication (Fig 2.4) (Bocquet-Appel, 2011; Zhao et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2021; Dong et al., 2022; Zeder, 2024; Daly et al., 2025). These domesticates spread from their origins through cross-continental crop/livestock diffusion, enabling prehistoric food globalization (Liu et al., 2019; Dong et al., 2022; Fuller et al., 2023). The earliest trans-Eurasian exchange characterized by the mixed utilization of crop/livestock originated from East and West Asia can be traced to~4.5 ka in southern margin of the central Steppe (Spengler et al., 2014), which extended to mid-lower Yellow River valley of North China and western Pamirs before 4 ka (Yatoo et al., 2020; Fig 2.4a). The major passageways for trans-Eurasian exchange shifted to the proto-Silk Road with remarkable increase in space and frequency during 4-2.2 ka (Fig 2.4b; Dong et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2023), which laid the foundation for the formation of the traditional ancient Silk Road.

Figure 2.4 The spatial-temporal pattern of Neolithic and Bronze sites with crops/livestock remains originated from East and West Asia across Eurasia (Dong et al., 2022).

Agricultural development, exploring new resources and the establishment of permanent settlements were key drivers of the Neolithic demographic transition (Bánffy and Whittle, 2024; Kiosak, 2024; Bocquet-Appel, 2011). Innovations such as irrigation systems, selective crop breeding, and the introduction of plows and harvesting tools significantly enhanced productivity (Fazeli Nashli et al., 2024; Vidale 2018). These advances laid the groundwork for the formation of early villages and towns and enabled major societal transformations, including the emergence of social hierarchies, labor specialization, long-distance trade, and complex Chalcolithic-era social systems around 7.2 ka (Maggino, 2017; Leppard, 2019; Matthews and Fazeli Nashli, 2022). In Southwest Asia, such developments culminated in the rise of the first city-states (6–5 ka), characterized by urban life supported by writing systems, bureaucratic institutions, and imperial governance structures (Liu, 2009; Matthews et al., 2024).

2.2 East-West Exchange of Culture, Arts, Science, Technology and Civilizations along the Silk Road

Food and Agricultural Technology Exchange

While the Silk Road is often recognized for its commercial significance, its deeper impact lies in facilitating the spread of technological innovations, ecological adaptations, and the exchange of diverse knowledge systems. One particularly underexplored aspect of this network is its role in connecting and integrating agro-pastoral systems.

In West Asia, the Fertile Crescent saw the early domestication of wheat and barley, while the eastern Eurasian steppe developed complementary strategies centered on drought-resistant millets and mobile pastoralism (Gerling et al., 2024). By the 3rd millennium BCE, these systems began converging through highland corridors such as the Pamirs and Zagros Mountains, where ecological diversity fostered experimental crop rotations.

Archaeological evidence from sites including Shortugai in Afghanistan reveals hybrid agricultural practices incorporated both West Asian pulses and East Asian millets by 2200 BCE, predating the classical Silk Road era (Liu et al., 2019). This integration strengthened food security, helping communities withstand climatic fluctuations, especially during the 3.9 ka megadrought, which severely affected monocultural systems (Fig 2.5; Chen et al., 2024).

Figure 2.5 Distributional change of different cultures between Sintashta-Petrovka, Andronovo from northern steppe, the Oxus civilization from Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) and the Harappan civilization in Indus Valley before and after 3900 yr Before Present (BP). (A) Before 3900 yr BP; (B) After 3900 yr BP (Chen et al., 2024).

Metallurgical, Culinary, Medical, and Artistic Exchange

Metallurgical exchange along the Silk Road vividly illustrates its technological significance. The Urals and Altai Mountains served as early hubs for copper smelting, while the spread of tin-bronze alloying techniques from Central Asia to the Yellow River valley around 2000 BCE revolutionized tool and weapon production. Nomadic groups in the Dzungar Basin played a key role as both innovators and transmitters, adapting metallurgical knowledge to develop lightweight, durable weapons and horse gear suited for mobile lifestyles. Importantly, these technological advances were not one-directional; burial sites in Xinjiang reveal Central-Plain-style bronzes modified with steppe animal motifs, highlighting the reciprocal nature of innovation and cultural exchange (Tan, 2022).

Culinary and medicinal exchanges further underscore the Silk Road’s role in shaping daily life. The introduction of Central Asian grapes and walnuts into Chinese orchards enriched nutritional diversity, while the westward spread of tea from Yunnan fostered new social rituals in Persia (Spengler, 2019). Medical manuscripts from Dunhuang reveal syncretic pharmacopeias, blending Greek humoral theory, Ayurvedic, and Taoist herbal knowledge, suggesting that cross-cultural healing practices flourished at caravan stops (Zhang and Li, 2022). These exchanges were facilitated by “steppe polyglots”, multilingual traders who developed early systems of cryptographic notation to record transactions across linguistic boundaries.

Artistic production along these routes defied cultural essentialism. Gandharan sculpture, blending Hellenistic realism with Buddhist iconography, was not merely stylistic imitation but a deliberate reimagining of spiritual aesthetics. Similarly, Sogdian textile motifs found in Turfan tombs integrate Chinese phoenix patterns with Sassanian geometric designs, reflecting artisanal collaboration rather than passive borrowing. These innovations were propelled by itinerant craftsmen who established workshops along trade nodes, adapting techniques to local materials while preserving transregional design elements (Guo, 2023).

The Silk Road’s intellectual legacy is rooted in its epistemic networks, where knowledge was systematically exchanged across civilizations. Astronomical observatories from Samarkand to Chang’an collaborated by sharing datasets on planetary movements, leading to more refined calendrical systems that were essential for agricultural planning and navigational precision. The transmission of numeral systems, particularly the Khwarazmian adaptations of Indian numerals, laid foundational concepts for algebra and algorithmic reasoning. Remarkably, recent decipherments of Tocharian manuscripts reveal debates between Buddhist logicians and Greek philosophers, hosted in Tarim Basin monasteries, highlighting unrecognized nodes of interdisciplinary dialogue (Lin, 2021).

Far from being a static corridor, the Silk Road functioned as a highly adaptive system, continually responding to environmental and political change. Major climate disruptions, including the two large tropical volcanic eruptions in AD 536 and AD 540, have been linked to widespread societal upheaval across the Northern Hemisphere (Peregrine, 2020). The Mongol administrative reforms introduced standardized passport systems and postal routes, inadvertently preserving endangered languages through formalized multilingual governance (Plano Carpini and Rubruk, 1985). These adaptive mechanisms contributed to the Silk Road’s resilience, enabling it to endure and evolve despite the rise and fall of empires.

Languages, Scripts, and Epigraphic Monuments as Testimonies of Cultural Life

Ever since the prehistory of the Silk Road, people have included rock art as a form of personal expression to document their lifestyle. Collection of rock art material belonging to pastoral and oyer mobile populations have been recovered from many sites, including the Yinshan and the Altai mountains. In historical times, people have adopted several scripts to leave behind their own testimonies of various nature, in a plethora of languages and media.

The linguistic history of the Silk Road includes processes of original invention, transmission, adaptation, and reform that gave life to a complex heritage that is to date far from having being fully documented. The history of scripts is especially telling about the cultural vitality of the Silk Road. The Sogdian script was adopted early on by Turkic people, but modified to create the Uyghur script. This was later transmitted to Mongols and Manchus, and further modified in the process. The Bugut inscription, found in Central Mongolia, was written in Sogdian language. The life of languages and scripts is an integral part of the cultural history of peoples interacting along the Silk Road, and their epigraphic sources form the sole repository of their autochthonous culture and historical memory.

The Turk, Uyghur, Tangut, Khitan, Jurchen and Mongol empires have separate linguistic histories but are united in their ambition to commemorate themselves through their own linguistic mediums, often short-lived, but nonetheless epigraphically and historically important. They have left behind documents in the form of stone inscriptions that are among the few surviving monuments of their history. As such, they preserve the authentic voice of Silk Road peoples that would be irretrievable by looking exclusively at documents written in non-Central Asian languages (Chinese, Arabic, Persian, etc.).

2.3 Hydroclimatic Challenges to Silk Road Sustainable Development

The Silk Road regions, dominated by arid climates and fragile ecosystems, face high vulnerability to hydroclimatic variability and environmental change. Limited adaptive capacity exacerbates challenges like water scarcity, food insecurity, and natural hazards, hindering progress toward Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on climate action, clean water, zero hunger, and sustainable livelihoods. Enhancing climate resilience through effective adaptation and mitigation is vital for long-term sustainability. Addressing these interconnected issues requires coordinated global efforts across scientific, policy, and community frameworks.

Climatic Changes and Weather Systems

Over the past seven decades, the Silk Road regions have experienced notable warming and highly variable precipitation (Fig 2.6; Masson-Delmotte et al., 2021). From 1980 to 2022, climate extremes accounted for 40% of global events and continue to increase (Almazroui et al., 2020; Bevacqua et al., 2022). South and Southeast Asia face disproportionately high economic losses due to dense populations and limited disaster response, with annual damages exceeding a quarter of the global total (Behera et al., 2024).

Figure 2.6 Temperature and precipitation trends (1950–2020) along the ancient Silk Road. (a) and (b) show the mean and changes in temperature. (c) and (d) show the mean and changes in precipitation. Temperature data are sourced from Climate Research Unit (CRU), while precipitation data are obtained from Global Precipitation Climatology Centre (GPCC). Dots in (b) and (d) indicate areas where the trends are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (source from Yanan Su and Shengqian Chen, Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences).

Climate variability along the Silk Road is shaped by interactions among major atmospheric systems, including the mid-latitude westerlies, Siberian High, Western Pacific Subtropical High, East Asian Summer Monsoon, and ENSO (Wang et al., 2014). Located between westerly and monsoonal regimes, the region experiences enhanced winter precipitation and moisture transport (Zhang et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2023). The Siberian High brings cold, dry winds and dust storms, while its weakening during a positive Arctic Oscillation allows warmer, wetter conditions (Gong et al., 2001). Conversely, a negative phase intensifies aridity. The Western Pacific Subtropical High is key to monsoon moisture; a westward shift can reduce rainfall across the region (Wang et al., 2014).

In addition, the region’s diverse landscapes, including high plateaus and expansive deserts, plays a pivotal role in shaping local climate conditions (Ragab and Prudhomme, 2002). Orography enhances rainfall (Lioubimtseva et al., 2009), deserts drive large diurnal temperature shifts, and snow cover alters surface energy balance via the albedo effect (Gong et al., 2001). During dry seasons, mid-latitude cyclones, cold fronts, and upper-level troughs contribute vital precipitation by triggering low-pressure systems and uplifting moist air (Yang et al., 2002). Together, these atmospheric processes, oceanic influences, and topographic features define the Silk Road’s hydroclimatic patterns, driving seasonal variability and long-term environmental trends.

Water Resource Changes under Climate and Human Impacts

The Silk Road regions are home to over 10,000 rivers and 70,000 lakes, covering more than 500,000 km2, about one-fifth of Earth’s lake area (Tan et al., 2018; Su et al., 2025). However, climate change, human activities, and poor resource management have led to widespread water scarcity (Huang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). One of the most striking examples is the Aral Sea (Fig 2.7(a)). Its surface area shrank from 400,000 km2 in the 1990s to approximately 100,000 km2 in 2015 due to irrigation (Micklin et al., 2010; Su et al., 2021). Despite restoration efforts, sustainable water management remains slow (Huang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023).

The “Aral Sea Syndrome”, marked by water scarcity and ecosystem decline (Fig 2.7(b)), affects other arid Silk Road basins like Lake Urmia and Lop Nur (Fan et al., 2009; Stone, 2015; Tourian et al., 2015). Intensified irrigation, wetland loss, and upstream storage worsen these crises (AghaKouchak et al., 2015; Li et al., 2018). Shared basins demand coordinated management (Vinca et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023), but tensions between development and restoration, mirroring the “Tragedy of the Commons”, hinder Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) progress (Hardin, 1968; Cheng et al., 2014; Guo, 2018). Unregulated use has caused 24% land degradation in the Aral Sea basin (Huang et al., 2016). Achieving SDGs 6.4 and 15.3 by 2030 remains a significant challenge (Jiang et al., 2020, 2022).

Figure 2.7 Spatiotemporal changes in the surface area of the Aral Sea (Central Asia) and Lake Urmia (West Asia) since the 1960s. Lake surface area data were derived from Landsat remote sensing images (1990–2020) with a spatial resolution of 30 m (modified from AghaKouchak et al., 2015 and Huang et al., 2022).

The Indus River basin, home to the world’s largest irrigation system, faces rising threats from climate change, population growth, and groundwater loss, jeopardizing water, food, and energy security (Arora et al., 2022; Rizwan et al., 2019). These issues hinder SDGs progress and highlight the need to understand human–climate–environment interactions along the Silk Road (Jamil et al., 2022; Smolenaars et al., 2021). Despite evidence of warming and water stress, the impacts of climate extremes on ancient societies remain unclear. An interdisciplinary approach using paleoclimate data, historical records, and modern tools is vital to uncovering environmental drivers and building future resilience.

Chapter 3 Research Priorities of ATES

Chapter 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the Silk Road from geographical, ecological, climatic, historical, and cultural dimensions, setting a holistic framework for interdisciplinary Silk Road research. In Chapter 3, we will delineate the ATES research agenda into six strategic priorities. The following six sections examine the core scientific priorities of ATES, each providing a distinct perspective on the long-term interactions between human societies, the environment, and trans-Eurasian exchanges. These sections emphasize the critical role of interdisciplinary collaboration, integrating insights from archaeology, history, geography, genetics, climatology, environmental sciences and socio-economic research.

Through analyses of ancient human migrations, the spread of agriculture, the evolution of trade routes, knowledge exchange in multiethnic societies, and the complex relationship between climate and civilization, this work underscores the deep interconnection within Silk Road studies. A comprehensive understanding of these priorities requires bridging disciplinary boundaries and fostering cross-cutting partnerships, ensuring that perspectives from diverse fields collectively illuminate the complex history and enduring legacy of trans-Eurasian exchanges.

3.1 Theme 1: Paleolithic Culture and Human Migration

General Introduction and State of the Art

The transcontinental migration, dispersal, interactions and adaptation of Paleolithic hominins remain central research topics in the scientific community, drawing significant public interest. Understanding human evolutionary pathways not only deepens our knowledge of the past but also strengthens our understanding of how our species has interacted with environmental and climatic fluctuations over the longer term. This research is particularly relevant for developing future strategies to address anthropogenic climate change. Although early modern humans were long known to have interacted genetically with archaic hominins, the advent of ancient DNA analysis in the early 21st century has greatly advanced our understanding of these relationships. These breakthroughs have confirmed the divergence of Homo erectus into Neanderthals and Denisovans at 650-450 ka (Reich et al., 2010; Prüfer et al., 2017), followed by their successive interbreeding across Eurasia, and the genetic exchanges between modern humans, even though the contribution of archaic hominins to present-day human genomes remains relatively limited (Green et al., 2010; Reich et al., 2010; Enard and Petrov, 2018; Slon et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020; Li et al., 2024; Ongaro and Huerta-Sanchez., 2024). The hypothesis that large glaciations triggered genetic drift in Eurasian Homo erectus (Sánchez Goñi, 2020) should be tested by checking for similar drift in other animal and plant taxa. In addition, due to scarcity of both human fossils and ancient DNA, researchers have relied heavily on archaeological evidence to reconstruct patterns of human dispersal and adaptation across different regions (Fig 3.1). Archaeological findings provide critical insights into early human migrations, subsistence strategies, and response to changing environmental conditions.

Figure 3.1 Interactions between Neanderthals and Denisovans in eastern Eurasia (source from Peiyuan Xiao and Hao Li, Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences).

This research theme will integrate multiple lines of evidence, including Paleolithic archaeology, paleoanthropology, and genomics, to provide a comprehensive understanding of early human dispersals, interactions and adaptation across the continent.

Objective of Theme 1

To advance understanding of early transcontinental dispersals of ancient human groups, their occupation of diverse environment, and their adaptation strategies over time.

Scientific Priorities of Theme 1

1) Extensive archaeological fieldwork: Conducting systematic excavations and uncovering new fossils and Paleolithic artifacts to significantly expand our understanding of early human evolution.

2) Development of new technologies: Utilizing ancient DNA and proteomic analyses to identify fragmentary human and animal remains; Applying sediment DNA to reconstruct the ecological communities across various sites and to detect genetic traces of ancient humans.

3) Multidisciplinary analysis: Investigating human evolution as a systematic endeavor that integrates knowledge from archaeology, anthropology, geology, geography, biology, chemistry, and related disciplines supported by modeling.

Theme 1 is built on extensive fieldwork and significant archaeological discoveries as its principal foundation. The current three research priorities listed above focus on implementing systematic field investigations and conducting scientific excavations at strategically selected Paleolithic sites along key regions of the Silk Road Corridor, with the objective of generating the collections of reliable archaeological data. Guided by a multidisciplinary approach, it emphasizes the adoption and innovative application of new methodologies. Theme 1 especially centers on the development of Paleolithic cultures and the transcontinental migration and adaptive patterns of prehistoric populations, which urgently requires collaborations among specialists from diverse academic domains. Through proactively adapting advanced methods, Theme 1 seeks to reveal the evolution of Paleolithic culture along the Silk Road Corridor and to clarify the cultural communication and interactions among ancient populations in this important area.

Planned Future Activities and Timelines

1) Short term (2025-2026): Establish collaborative fieldwork teams in partnership with national and international universities, regional archaeological institutions and research organizations. Select the key areas where Paleolithic and Paleontological sites are densely concentrated along the Silk Road corridor for joint surveys and targeted excavations. Introduce and provide training in advanced methodological and technological approaches to strengthen the expertise of the local teams.

2) Medium term (2027-2028): Conduct in-depth joint excavations and multidisciplinary integrated research. Implement sustained excavations at key sites, accompanied by specialized analyses across relevant fields. Organize field work projects to promote the training and exchange of researchers. Publish a series of research articles in leading international journals and convene regular thematic symposia.

3) Long term (2029-2030): Develop a comprehensive database for important Paleolithic sites along the Silk Road corridor and construct a stable international academic exchange network and platform. In collaboration with local museums and educational institutions, produce a series of publications and documentary films. Integrate archaeological research outcomes into Silk Road cultural tourism initiatives and regional development strategies to further support the development of Paleolithic site archaeological parks and related cultural facilities.

Potential Regional and International Links

Our international links mainly relate to the organizations focusing on prehistorical studies in Asia, including the International Union for Quaternary Research (INQUA), Past Global Changes (PAGES), Asian Paleolithic Association (APA), the Society for East Asian Archaeology (SEAA), the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association (IPPA), the International Union of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences (UISPP), the European Association of Archaeologists (EAA), and the International Association for Archaeological Research in Western & Central Asia (ARWA).

3.2 Theme 2: The Origin of Agriculture and Trans-Eurasian Diffusion of Early Farming and Herding

General Introduction and State of the Art

The agricultural revolution around 10 ka was a significant milestone in human history (Yan, 2000; Zeder, 2008). Independent domestication of crucial crops and livestock took place in various regions, such as the Fertile Crescent, the Yangtze, and Yellow River Valleys (Zeder, 2008, 2024; Riehl et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024, Mattews and Fazeli Nashli, 2022; Thomalsky and Fazeli Nashli 2024). This long-lasting process that eventually resulted in the shift from hunting to settled agriculture led to population growth, cultural expansion, and the rise of Neolithic revolution, then the Chalcolithic stage and finally the Bronze Age civilizations (Gignoux et al., 2011; Fazeli Nashli and Matthews 2021; Matthews and Fazeli Nashli 2004). Interactions across Eurasia played a pivotal role in the development of early societies, with evidence of cultural exchanges predating the Silk Road (Dong et al., 2022, 2023). Key crops like wheat, barley, rice, millet, along with livestock such as sheep, cattle, and pigs were first cultivated or domesticated in specific regions. The spread of broomcorn millet to Central Asia and Europe, and the utilization of wheat and barley in northern China, illustrate the profound impact of early agricultural practices (Liu et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2023). However, the spatiotemporal dynamics of agro-pastoral systems in Eurasia during the Neolithic-Bronze Age, as well as the dispersal processes of crops and livestock, remain insufficiently understood, primarily due to geographical disparities in archaeological investigations, especially in Central and West Asia. During the Neolithic to Bronze Age, technological advancements in agriculture and metallurgy, along with their widespread adoption, resulted in the transformation of human lifestyles and habitat expansion, especially in Xinjiang, the Qingzanggaoyuan and the eastern Steppe (Fig 3.2). Population growth was intricately linked to technological advancements and global trade.

Figure 3.2 Distribution of Neolithic and Bronze Age sites from 10.5-4 ka (a) and 4-2.2 ka (b), before and after the intensification of trans-Eurasian exchange (source from Linyao Du, Lanzhou University, China).

Humans adapted to changing environments in response to climate variations. Population growth drove the expansion of settlement areas, technological innovation, and heightened environmental impacts. However, the mechanisms driving the dispersal of crops and livestock into high-altitude regions remain poorly understood. This period witnessed a heightened human impact on fire patterns, plant biodiversity, and land characteristics, notably during the Bronze Age (Mu et al., 2016; Bergeret al., 2024). Concurrently, increased transcontinental cultural exchange during 4–3 ka (Dong et al., 2023) facilitated the widespread adoption of Bronze Age technologies across Eurasia. Nevertheless, the interplay between these cross-continental exchanges, landscape transformations, and the emergence of early social complexity remains ambiguous. These dynamics fundamentally reshaped human-environment interactions in Eurasia, highlighting the critical need to investigate proto-historic socioecological systems at continental scales.

Objective of Theme 2

To deepen our understanding of prehistoric trans-Eurasian exchanges, this research investigates the origins of agriculture, the spread of early farming and herding communities, and their impacts on human societies and human–environment interactions across Eurasia during the Neolithic to Bronze Age.

Key Scientific Priorities of Theme 2

1) Spatiotemporal dynamics of agro-pastoral systems in Eurasia during the Neolithic-Bronze Age, as well as crop and livestock dispersal processes.

2) Innovation and transmission: how complex technological innovation develop Eurasian Network.

3) Interactions between societies of the Eurasian steppe and Silk Road and their impact on human-environment-climate interaction in the Neolithic-Bronze Age.

Theme 2 investigates the intertwined processes that shaped human societies and landscapes across Eurasia during the Neolithic to Bronze Age transition. By examining the spatiotemporal dynamics of agro-pastoral systems, the aim is to trace how crops, livestock, and subsistence strategies spread and adapted across diverse ecological zones. These shifts were closely linked to the development and transmission of complex technological innovations, which formed and reinforced expansive networks of exchange and interaction across Eurasia. At the same time, the growing connectivity among societies particularly along the Eurasian steppe and early Silk Road played a transformative role in shaping human-environment interactions. Together, these research strands provide a holistic understanding of how mobility, innovation, and interregional contact contributed to the emergence of complex socio-ecological systems in prehistoric Eurasia.

Planned Future Activities and Timelines

1) Short term (2025-2026): To evaluate the cultural exchange model in depth and to supplement the data from the key regions, we need to integrate and establish a database for sharing archaeobotanical, zooarchaeological, carbon/nitrogen isotopic, genetic data and radiocarbon ages from Neolithic and Bronze Age sites in mid-latitude Eurasia, and carry out international fieldwork and surveys, collecting samples from Central and West Asia and Eastern Europe.

2) Medium term (2027-2028): To host a sequence of international symposia focusing on prehistoric trans-Eurasian exchanges and human-environment interaction during Neolithic-Bronze Age.

3) Long term (2029-2030): For interdisciplinary collaboration and communication, we plan to participate in important international cooperation programs (e.g., European Research Council Synergy Grant) or working groups, nurture talent and train students with other groups. The content of the future project will include I: Agro-pastoral development and civilizations evolution since the Neolithic Age. II: The history and impact of exchanges and mutual learning among civilizations. III: Spatial-temporal variations in human living environments during the Holocene. IV: Interactions between civilizations evolution and environmental change.

Potential Regional and International Links

Our international links mainly relate to the organizations focusing on Neolithic exchanges in Eurasia and their interactions with climate changes, including the Society for East Asian Archaeology (SEAA) and International Geographical Union (IGU). Collaboration with the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) is planned.

3.3 Theme 3: Evolution and Development of the Transport Network and Towns

General Introduction and State of the Art

The Silk Road, spanning over two millennia, emerged during the Bronze Age through corridors like Persia’s “Royal Road” and China’s “Chi Dao (驰道)” Unified under the Han Dynasty (2nd century BCE), it evolved into a transcontinental network linking Chang’an (Xi’an) to the Mediterranean by the 1st–8th centuries CE, facilitating trade in silk, spices, metals, and the spread of religions (Buddhism, Christianity, Islam), technologies, and languages (Fig 3.3). Cosmopolitan hubs like Samarkand and Kashgar thrived, while Islamic expansions (9th–14th centuries CE) integrated Baghdad and Tabriz into global trade, cementing its role in early globalization (Boulnois et al., 2012).

Figure 3.3 Major cities along the ancient Silk Road (modified from the UNESCO Silk Road Programme, https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/).

Modern interdisciplinary research leverages geospatial technologies (LiDAR, GIS) and archaeological-historical synthesis to map the Silk Road’s evolution. Frachetti et al. (2017) demonstrated how nomadic pastoralism shaped Central Asian highland routes, while Briant (2002) highlighted Persia’s infrastructural legacy. Cutting-edge studies focus on route dynamics, urbanization patterns, and cross-cultural hybridization, revealing adaptive strategies to environmental shifts and geopolitical upheavals. Satellite imagery and textual analysis now decode how climate, technology, and power struggles reshaped this ancient network, offering insights into resilience strategies relevant to modern globalization.

These advances underscore the Silk Road’s dual nature as both a product of natural landscapes and human ingenuity, offering insights into resilience strategies relevant to modern globalization.

Objective of Theme 3

The primary objective is to reconstruct the formation, maintenance, and transformation of Silk Road networks and towns through an interdisciplinary lens. By integrating archaeology, geospatial technology, historical analysis, and anthropology, this theme seeks to elucidate the environmental, technological, and sociopolitical drivers that shaped one of history’s most enduring exchange systems.

Key Scientific Priorities of Theme 3

1) Network evolution: Understanding the Silk Road transport network and towns’ lifecycle, from emergence to decline, integrates environmental, geopolitical, and technological insights.

2) Urbanization-environment nexus: Interdisciplinary case studies decode Silk Road town dynamics.

3) Cross-cultural exchange: Triangulating textual, artifact, and genetic studies traces cultural diffusion.

Theme 3 integrates three interconnected objectives to generate a comprehensive, multidimensional understanding of the Silk Road’s development and its broader significance. By analyzing the development and transformation of the Silk Road transport network and the lifecycle of its towns from emergence to decline, environmental, geopolitical, and technological perspectives are integrated to illuminate broader patterns of connectivity. Building on this foundation, interdisciplinary case studies of individual settlements examine the urbanization-environment nexus, revealing how Silk Road towns both responded to and shaped their ecological contexts. Complementing these spatial and environmental analyses, the study of cross-cultural exchange through the triangulation of textual sources, material artifacts, and genetic evidence, traces the movement of people, goods, and ideas across the network. Together, these three strands form a coherent and integrative approach to understanding the Silk Road as a dynamic and adaptive system of infrastructure, settlement, and cultural transmission.

Planned Future Activities and Timelines

1) Short term (2025-2026): Establish the ATES Silk Road Network Database, compiling geospatial, archaeological, and historical datasets for open-access sharing. Launch joint field surveys in Central Asia (Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan) to map unstudied courier stations and trade nodes.

2) Medium term (2027-2028): Organize international workshops to standardize methodologies for analyzing urbanization patterns. Develop predictive models to assess climate-driven risks to heritage sites (e.g., desertification impacts on Loulan).

3) Long term (2029-2030): Publish a synthesis report integrating findings from Working Groups 1 (human migration) and 6 (climate-civilization interactions). Train early-career researchers in geospatial archaeology and multilingual text analysis through ATES-funded fellowships.

Potential Regional and International Links

Academic collaborations with Eötvös Loránd University (Hungary) enable rigorous analysis of multilingual archives, such as Persian trade ledgers, reconstructing Eurasian trade dynamics. The Research Center for the Humanities (Hungary) contributes methodologies for studying urbanization-climate interactions. Institutional alliances with the UNESCO Silk Road Programme ensure alignment with global heritage standards, protecting sites like Samarkand from modern threats. The Max Planck Institute for Geoanthropology integrates paleoclimate data (e.g., ice cores) with archaeological findings, decoding environmental impacts on settlements. Funding platforms like ERC Synergy Grants support large-scale projects modeling Silk Road resilience to droughts or conflicts, while ANSO Joint Research Centers in Xi’an and Samarkand foster local capacity-building and cross-border data sharing. Collectively, these partnerships unify fragmented datasets, secure access to high-risk regions, and ensure research informs sustainable development, preserving the Silk Road’s legacy as a paradigm of human-environment adaptability.

3.4 Theme 4: Evolution and Circulation of Culture, Science and Technology along the Silk Road

General Introduction and State of the Art

Beyond trade, the Silk Road has been a dynamic conduit for evolving and exchanging language, cultural, science and technology, profoundly shaping Eurasian cultural, intellectual and technological landscapes (Zhao, 2025; Zhao, 2021).

The Silk Road served as a vital crossroads, leaving behind a wealth of written documentation preserved in the archives of major civilizations like China, Persia, Byzantium, and Islamic states. However, crucial records from the empires and peoples who actively shaped the Road often survive only as monumental stone inscriptions. Steles like Bugut and Orkhon provide unique access to the authentic voices of these cultures. Peoples fundamental to connecting East and West – Sogdians, Turks, Tanguts, Kitan, Jurchen, and Mongols – developed or adopted diverse scripts (Kharoshti, Brahmi, Runiform Turkic, Uyghur-Mongol, Tangut, Kitan, Jurchen). Used for over a millennium, these scripts hold vast, largely untapped knowledge. Unfortunately, understanding these documents remains confined to a small group of specialized linguists and philologists globally. Their work is scattered across obscure, multilingual publications in Hungarian, Turkish, Polish, Russian, Mongolian, Japanese, Chinese, French, English, German, etc.

The Silk Road also played a crucial role in the development and dissemination of scientific knowledge. Astronomical observations and theories from China, Persia, Greco-Roman, and Islamic scholars were shared, enriching astronomical studies across Eurasia (Fig 3.4). Mathematical concepts, including the Indian decimal system and the use of zero, traveled westward, influencing Islamic and European mathematics. In medicine, herbal remedies and surgical techniques were exchanged between Chinese, Indian, and Islamic scholars, contributing to advancements in healthcare (Niu, 2019).

Figure 3.4 The first pages of the 14th century Chinese translation of a set of Persian astronomical tables, believed to have been compiled by the Muslim Observatory of the Yuan Dynasty in Beijing (source from Courtesy of the National Archives of Japan).

Technological advancements in metallurgy and ceramics were also pivotal. Chinese kiln technologies capable of reaching 1450°C enabled the production of high-quality porcelain, which influenced ceramic traditions in Central Asia and the Islamic world. Similarly, metallurgical innovations, such as the introduction of chain mail armor by the Sogdians to China in the 7th century, highlighted the cross-cultural exchange of metalworking skills (Huang, 2022; Chen, 2023).

Technological innovations such as paper-making, printing, gunpowder, and the magnetic compass were transmitted along the Silk Road. Paper-making, originating in China during the Han Dynasty, spread to Central Asia and the Islamic world, revolutionizing record-keeping and knowledge dissemination. The magnetic compass, developed in China, became a vital navigational tool that enabled long-distance sea voyages, transforming global trade and exploration. The legacy of these exchanges is evident in the interconnectedness of civilizations and the lasting impact on global development. The Silk Road served as a model for future trade networks, emphasizing the importance of collaboration and knowledge sharing in shaping human progress.

Objective of Theme 4

To explore the evolution of culture, science and technology in Eurasia and compile a comprehensive trace and history of their dissemination and mutual inspiration among the ancient civilizations along the Silk Road.

Key Scientific Priorities of Theme 4

1) Create a comprehensive digital corpus of all known Silk Road inscriptions and related publications (partial or complete translations, linguistic studies, and commentaries), systematically categorized and searchable by medium, language, period, location, etc.

2) Collect, collate, and digitize historical texts, images, and physical artifacts specifically documenting the exchange of scientific and technological knowledge along the Silk Road.

3) Conduct multilingual and multidisciplinary research to analyze the development, dissemination, and transformation of culture, science and technology innovations within complex cross-cultural socio-economic environments along the Silk Road.

Theme 4 integrates three complementary strands to deepen understanding of culture, science and technology evolution and exchange along the Silk Road. First, the comprehensive collection, collation, and digitalization of inscriptions, historical texts, images, and artifacts establishes a foundational repository, enabling systematic analysis and broader accessibility. Building on this base, multilingual and multidisciplinary studies on how language, culture, science and technology innovation were developed, transmitted, and transformed within the shifting political regime and intellectual landscapes across Silk Road regions. Complementing these historical and linguistic analyses, multidisciplinary investigations explore the dissemination and adaptation of culture, science and technology within complex cross-cultural and socioeconomic contexts. Together, these efforts provide an integrated perspective on the dynamic flow of it that shaped cultural and intellectual evolution across Eurasia.

Planned Future Activities and Timelines

1) Short term (2025-2026): Assemble a team of experts who can access the relevant literature, based on international collaborations in several countries, including especially Hungary, Turkey, Japan, China, and Mongolia. Construct a multi-mode data base of astronomical and mathematical texts, images and objects from historical periods.

2) Medium term (2027-2028): Establish a comprehensive database as a digital repository of the epigraphic corpus, to be augmented as the selection of material proceeds. Continue to expand the database to other fields of science and technology, and initiate a project of an online Encyclopedia of the Exchange of Science and Technology Along the Silk Road on the basis of the database and the studies based on the database.

3) Long term (2029-2030): Maintain the database and adjourn it with every new publication; and work on known but as yet untranslated or even undeciphered inscriptions with new translations based on the team of experts that has been established.

Potential Regional and International Links

The nature of theme 4 is especially conducive to collaborations between several experts, including Altaic languages specialists, Turcologists, Indo-Europeanists, historians, archaeologists, and philologists. Institutional collaborations can be established with the International Dunhuang Programme (IDP), which includes several collections and archives that may be mined for relevant documentation. Potential regional and international links involve connections with several prominent institutions. These include the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Germany, which is renowned for its contributions to the study of the history of science. The National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS, France) also plays a significant role in fostering international academic cooperation. The Institute of Archeology named after A.Kh. Khailkov of Tatarstan Academy of Science in Russia brings its unique perspective in the field of archeology to these potential links. The Needham Research Institute in the UK, known for its work related to the history of science in China, is another important partner. The Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in Qatar contributes to research and policy discussions on a regional and international scale. The University of Hong Kong (HK) is a vital institution with a diverse academic environment, and the Institute of the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW) at New York University, which focuses on the study of ancient cultures, further enriches these potential regional and international connections.

3.5 Theme 5: Genetic History of Silk Road Populations

General Introduction and State of the Art

Diverse ethnic groups with unique religious beliefs, cultures, and customs inhabited the Ancient Silk Road, adding complexity and intrigue to its history. Since the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, this region witnessed numerous cross-continental exchanges that shaped material and cultural aspects (Xu & Li, 2017). These interactions greatly influenced the way of life and subsistence practices along the Silk Road. Despite their importance, research on human population dynamics in this context remains limited. For example, practically no ancient human genomes in the Gansu and Qinghai provinces have been published, a vital region connecting the Eurasian Steppe and the Central Plain of China (Fig 3.5).

Figure 3.5 Genetic formation and migrations of the ancient Silk Road populations. Ancient Silk Road populations represent admixtures of Western Eurasian Steppe herders, Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC)/Central Asians, Ancient Northeast Asians, Yellow River farmers, and Highlander-related ancestry (source from Xiaomin Yang and Chuan-Chao Wang from Xiamen University, China).

Studying ancient DNA has gained insights into the genetic composition of populations living along the eastern Silk Road during the Neolithic and Bronze Age (Ning et al., 2020; Wang W et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025; Xiong et al., 2024). Current understanding suggests that the Qijia culture, represented by samples from Lajia and Jinchankou in the eastern Hexi Corridor, was a mixture of approximately 80% Neolithic middle-to-lower reaches of Yellow River farmer (NYR)-related ancestry and 20% Ancient Northeast Asian (ANA)-related ancestry. Notably, there is little evidence of genetic contributions from Western Eurasia (Ning et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2024). In Northern China, there is a strong genetic continuity of NYR-related ancestry from the Central Plains and ANA-related ancestry from northeastern China (Fang et al., 2025). The northwest China (present-day Xinjiang and Gansu) and Mongolia exhibit a complex population history influenced by intermingling various Western and Eastern Eurasian-related ancestries over different regions and periods (Wang et al., 2021; Wang W et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025).

In recent years, by relatively direct means of studying ancient samples such as bones and/or indirectly analyzing the genomes of modern populations, the demographic history - migrations, expansions and colonization - has been successfully revealed in several previous human population genetic studies (Wang W et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022; Li et al., 2025; Xiong et al., 2024; Ning et al., 2023; Lei et al., 2024; Wen et al., 2024). However, critical questions remain unresolved.

Spatio-Temporal Admixture Dynamics: How did the timing and routes of East-West genetic mixing vary across regions like Gansu/Qinghai (the “eastern gateway” to the Steppe) versus Xinjiang (the core Central Asian corridor)? Existing data from Gansu/Qinghai are almost nonexistent, hindering our understanding of when Western Eurasian influences first reached the Chinese frontier. Agriculture and Population Expansion: Did the spread of millet (eastward) and wheat/barley (westward) farming technologies coincide with demographic expansions or cultural diffusion? For instance, whether the Qijia culture’s NYR ancestry reflects direct farmer migration or adoption of agricultural practices remains unclear. Linguistic and Genetic Correlations: How do genetic admixture patterns map to the dispersal of language families (e.g., Indo-European, Turkic, Sino-Tibetan) along the Silk Road? Studies in Mongolia and Xinjiang suggest complex interactions, but systematic integration of genetic, linguistic, and archaeological data is lacking. Health and Adaptive Traits: Did Silk Road populations develop unique genetic adaptations to environmental stressors (e.g., aridity, high altitude) or disease exposures (e.g., malaria, tuberculosis)? No comprehensive phenomic studies exist for these populations.

Objective of Theme 5

To systematically characterize the genetic structure, admixture histories, origins, and migration dynamics of Silk Road populations through integrated analyses of paleogenomics, pan-genomics, and physical anthropology. This research aims to decipher the deep-time interactions between human genetics, linguistic dispersals, technological diffusions (e.g., agriculture), environmental adaptations, and disease evolution across Eurasia. By filling critical data gaps in understudied regions like Gansu and Qinghai, the “eastern gateway” to the Eurasian Steppe, this work will establish a multidimensional framework linking genetic, cultural, and phenotypic landscapes, providing molecular evidence for understanding human civilizational exchanges along the Silk Road.

Key Scientific Priorities for Theme 5

1) Spatiotemporal admixture dynamics in Gansu/Qinghai and Xinjiang, and genetic-linguistic correlations and language family dispersals.

2) Demic vs. cultural diffusion in agricultural technology spread.

3) Genetic adaptations and disease transmission in Silk Road populations.

Theme 5 employs an integrative methodology integrating genetics, linguistics, archaeology, and phenotypic analysis to explore the long-term dynamics of human populations across Eurasia. The first priority aims to uncover the temporal and spatial characteristics of genetic mixing in regions such as Gansu/Qinghai (the ‘eastern gateway’ to the Eurasian Steppe) and Xinjiang (the core Central Asian corridor). By studying the genetic composition and migration patterns of populations in these areas, we can understand the process and route of East-West genetic exchange and explores the genetic and linguistic correlations of major language families, including Indo-European, Tungusic, Mongolic, and Turkic. By analyzing the relationship between population migrations, admixture events, and the spread of language families, we can gain insights into how these factors influenced the cultural and civilizational development of Silk Road societies. The second priority focuses on determining whether the spread of key prehistoric agricultural innovations, such as the eastward spread of millet and the westward spread of wheat and barley, was primarily driven by demic diffusion (population movement) or cultural diffusion (knowledge transfer). Paleogenomic and pangenomic tools will be used to map genetic variation across time and space to address this question. The third priority examines the transmission of physical and disease-related phenotypes among historically connected populations. It aims to identify the genetic and epigenetic bases of adaptive traits and health vulnerabilities, thereby understanding how Silk Road populations adapted to environmental stressors (such as aridity and high altitude) and disease exposures (such as malaria and tuberculosis).

Through these research priorities, Theme 5 seeks to provide a multidimensional understanding of human diversity, mobility, and adaptation in the context of trans- Eurasian interaction, and to establish a comprehensive framework linking genetic, cultural, and phenotypic landscapes.

Planned Future Activities and Timelines